FAQ

Answers to the most common questions about the TR Site.

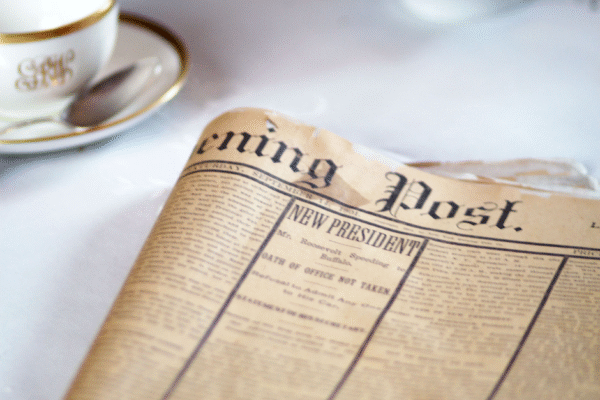

“I do not believe that any man can adequately appreciate the world of to-day unless he has some knowledge of—a little more than a slight knowledge—some feeling for and of—the history of the world of the past.”

– Theodore Roosevelt, 1911

Our free lesson plans are suitable for students in grades 4-12 and utilize the Inquiry Design Model.

Bring your students to the TR Site for an immersive, guided tour of the house where the modern presidency began!

Check out the wide variety of outreach programs the TR Site offers for K-12 students and general/adult audiences.

Our blog shines a spotlight on items from our artifact collection and offers opportunities for behind-the-scene perspectives on the TR Site.

Answers to the most common questions about the TR Site.

Tours are just the beginning! Check out our special programs...

The "In-SITE" blog provides an insider's view of the TR...

Get in touch! We'll answer your questions.